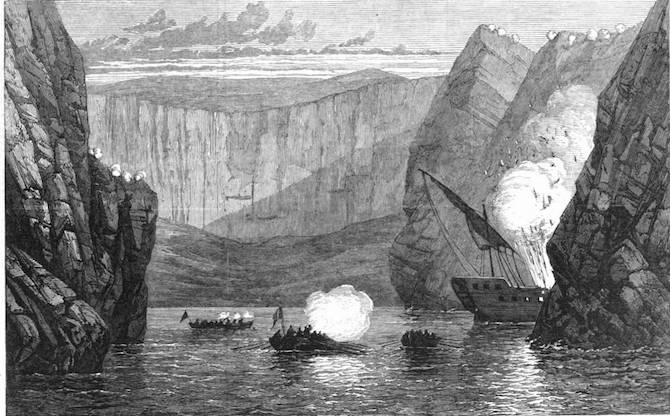

Blowing up of a slave dhow in the Arabian Gulf by the boats of the H. M. S. Spiteful. Source: Illustrated London News (4 July 1868)

More research on the social history of the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula is needed insofar as many segments of these societies have been marginalised by local historians who have generally focused on more powerful people such as sheikhs, merchants or the religious elite. For instance, the main works of Kuwaiti historians published between the 1920s and 1960s (e.g., ʿAbd al-ʿAziz al-Rushaid, Yusuf bin ʿIsa al-Qinaʿi, Saif Marzuq al-Shamlan and Rashid al-Farhan) mainly cover prominent figures except for sporadic references to other segments of society. An exception to this is al-Hatim, who refers to workers, divers, women, shopkeepers, soldiers, guards and fishermen, though quite briefly. Despite the recent (re)surfacing of local documents and manuscripts on this topic, slaves are almost absent from the dominant historical narrative of the region. More recently, researchers have attempted to address this gap, studying non-elite categories such as divers and sailors, while others have documented the histories of local tribes, women and workers, traditional clothing and ornaments. Concerning slavery, a very recent book by Hesham Alawadi (published in 2021) addressed this issue, although not shedding light on its societal implications in the Gulf. According to the author himself in his introduction, the book heavily depended on British archives, and a notable point he raised is that more scholarly research is needed, particularly based on oral history as some freed slaves are still alive today (Alawadi, 2021. p15) in the Gulf region.

Furthermore, with the development of technology and the resulting ease of communication, new audio-visual sources have emerged, thereby shedding light upon the slave communities in the Gulf during the 19th and early 20th centuries. A key source for this post is a recorded, televised interview with freed slaves and descendants of freed slaves in Kuwait and the Gulf. Sources such as these have significantly enhanced our understanding of slaves’ history and Black populations in the region. In addition, on social media, people have been increasingly addressing slavery in the Gulf and its social and ethnic roots with specific reference to local Black populations. For example, in a video shared on social media, a Black Kuwaiti states that ‘the Al-Rumi family brought Black people to Kuwait as slaves’ and he criticised other Black Kuwaitis for denying their heritage. In response to this claim, a Black Saudi man, in another social media video, retorted that ‘this does not apply to other Black people in the Arabian Peninsula’. Moreover, a growing number of audio-visual materials recorded since the 1950s have become available to a broader audience through social media platforms. These sources include al-Shamlan’s television programme that he co-presented and prepared in 1964, which remains a rich source of Kuwait’s oral history. Al-Shamlan interviewed people from various social groups, including a shepherd, local tribesmen, freed slaves and villagers.

Due to such sources being made available to a wider audience, it may appear that researching the issue of slavery and post-slavery in Gulf history has become easier for social historians. However, researchers embarking on this journey can face serious legal consequences. Hence, despite the importance of this issue for our understanding of the Gulf’s social history, local researchers may be caught in a complex dilemma between the need to shed light on this important historical issue and its sensitive nature from a legal and social perspective.

Several recent laws have significantly prevented people – local historians, in particular – from discussing sensitive issues, considered social taboos, as they relate to ethnicity and social status, including slavery and its social implications. These laws were enacted under the banner of National Unity. For example, the governments of Kuwait and Bahrain issued strict laws at the beginning of the new millennium. In 2002, Bahrain’s government issued its Press, Printing, and Publishing Regulations, Article 69 of which relates to inciting hatred against a sector or sectors of people and/or to any incitement that leads to the disruption of public security or spreading discord in society and prejudice to national unity. In Kuwait, the situation is stricter: in 2011, the parliament issued a law relating to ‘National Unity’, Article 2 of which prohibits any form of expression calling for, or exhorting, at home or abroad, the hatred of or contempt for any segment of society. It also bans any incitation to harm ‘national unity’ or foster sectarian strife or tribalism; spreading ideas that call for the supremacy of any race, group, colour, origin, religious sect, gender, or lineage, and any attempt to justify or reinforce any form of hatred, discrimination, or incitement. Notably, the law also forbids the writing, broadcasting or publishing of articles or ‘false rumours’ that may infringe upon ‘national unity’. Under this legal framework, mentioning the names of freed slaves’ families and their descendants is punishable by law, in addition to being extremely sensitive socially even when addressed academically and within the framework of social justice and equity. Hence, it is currently socially and legally preferable in Kuwait to avoid discussing such various topics, especially in the Arabic language.

An example of legal issues involving academics is Shafeeq al-Ghabra, a Kuwaiti political science professor at the University of Kuwait, who published Al Nakba was Nashu al-Shatat al-Filastinii fi al-Kuwait (The Nakba and the Emergence of the Palestinian Diaspora in Kuwait). This book was developed from his 1987 doctoral thesis and later published in English in 2019. In these publications, al-Ghabra, being of Palestinian descent, condemned the violence inflicted on Palestinians in Kuwait following the liberation of the country from Iraqi occupation in 1991. Following these publications, al-Ghabra was sued by a former member of the Kuwaiti National Assembly for supposedly insulting Kuwait and its people; al-Ghabra was nonetheless acquitted of that charge by the court. This shows how sensitive historical writings in Kuwait and other Gulf countries may be, potentially leading authors to be imprisoned. Nonetheless, although I am not aware of any ongoing legal case involving the mention of slavery or Black people, this issue remains extremely sensitive from a legal and social perspective.

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق